Defining Quality and The DFOW Flywheel in Pre-Design and Programming

The Definable Feature of Work (DFOW) in Early Project Phases and Conversations

Contents

Introduction

A New Definition for Quality: Delivering Client Intent

The DFOW Flywheel and the First Conversation

Applicable Elements of the DFOW Flywheel in Development and Pre-Design

Client Intent in Development and Pre-Design

Critical Activities in Development and Pre-Design

Experience and Lessons Learned in Development and Pre-Design

Challenges in the Early Conversations

In Practice

Conclusion

Special Thanks

Introduction

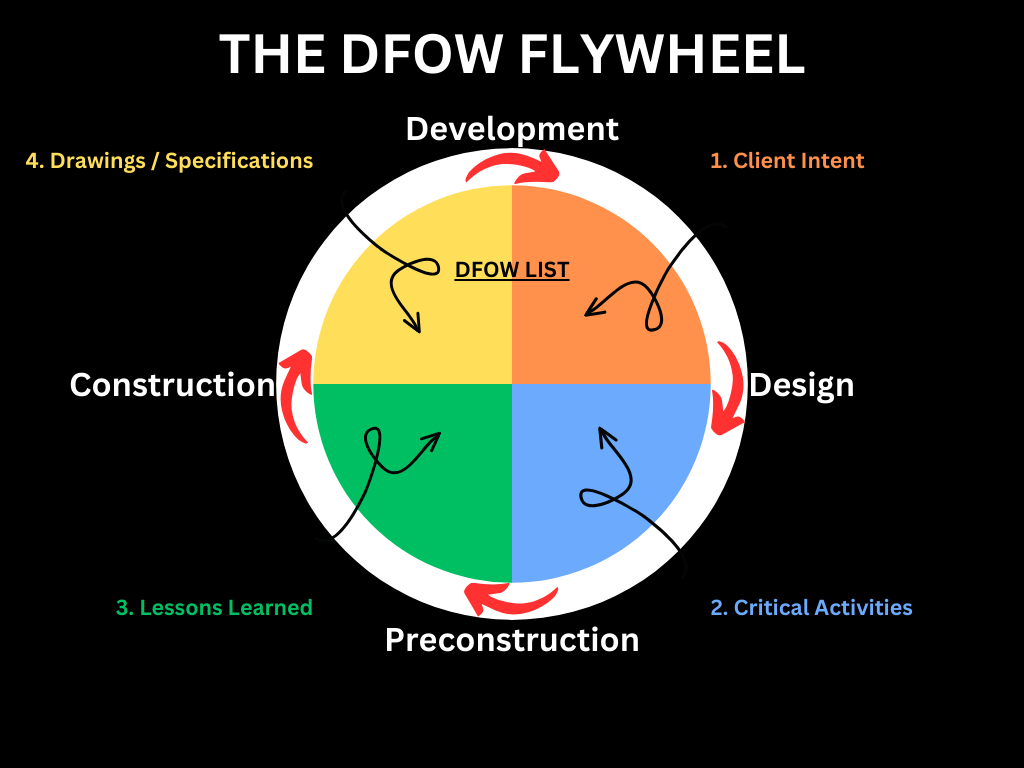

In the previous article in this series, I introduced the concept of the DFOW Flywheel, expanding the traditional definition of Definable Features of Work (DFOW) beyond specifications to include Client Intent, Critical Activities, and Lessons Learned and that the DFOW list starts at project inception rather than construction mobilization and be utilized throughout the entire project.

I wrote previously regarding my concerns with our current understanding of a DFOW:

“I note these definitions to illustrate the complex terminology surrounding quality in the industry. A “task that is separate and distinct from other tasks” or a “work activity as it relates to the specifications” is not objective or tactical, making it difficult to manage for those installing the work - those with the greatest control over a quality result.”

In this article, I propose a new definition for quality in design and construction - “Delivering client intent” - and apply the DFOW Flywheel to the early project stages using a multifamily project to articulate how it can be implemented.

A New Definition of Quality: Delivering Client Intent

In manufacturing, unhappy customers can return products. This is impossible in our industry where stakeholders and clients often lack the vocabulary to articulate what quality means to them. Michael Kubal noted in Engineering Quality in Construction: Partnering and TQM that:

“The complexity of the customer matrix in construction projects prevents the direct focus on customers that is possible in manufacturing or service industries. This complexity makes it difficult to achieve the quality standards envisioned by the ultimate customer, the building owner.”

Our industry fails to realize that our client’s expectations are derived from their intent. Intent as a noun means purpose. As a verb, intent means showing eager attention. W. Edwards Deming noted in Out of the Crisis that:

“Quality begins with the intent, which is fixed by management. The intent must be translated [emphasis my own] by engineers and others into plans, specifications, tests, production”.

He repeated it again on page 49:

“We repeat here from page 5 that the quality desired starts with the intent […].”

This insight changed my perspective and part of the origin story for the framework that became the DFOW Flywheel. I now believe that we may be incorrectly defining quality in our industry. There should be one intent—the client's—and our job is to translate and deliver it. This doesn't excuse us from contractual obligations. It simply helps us focus on what truly matters to the client.

The DFOW Flywheel and the First Conversation

A component I felt was missing from the industry’s traditional understanding of a DFOW was the lack of direct client input, where it is assumed by construction that the drawings and specifications perfectly articulate the client’s intent. In traditional design planning, teams develop specifications from programmatic requirements. Teams try to focus on everything, attempting to organize the contractual obligations and interpret the client’s true needs. In the transition between project phases, what’s truly important to the client gets lost in translation amidst all the details.

Our traditional approach often rushes through these early conversations, focusing primarily on budget, timeline, and basic programmatic requirements. This mindset needs to be constructively challenged.

I noted in Understanding the DFOW Flywheel:

“The most important elements of our projects are hidden beneath casual layers of commentary during the first conversations with our clients. These details get lost during the busyness of project work.”

We must recognize that quality begins with the first conversation - where a client’s business goals expectations materialize long before design, estimating, or construction begin. The DFOW Flywheel framework emphasizes deep listening and structured documentation of client intent during these initial interactions. Development and Pre-Design phase represents our critical window to establish the DFOW Flywheel's momentum by identifying what truly matters to our clients.

Applicable Elements of the DFOW Flywheel in Development and Pre-Design

Client Intent: Elements explicitly valued by the client - their business goal and purpose.

Critical Activities: High-risk or schedule-critical elements.

Lessons Learned: Explicit and tacit knowledge from past projects.

Drawings and Specifications: Technical requirements from the specifications and drawings.

In these early project conversations, the DFOW Flywheel’s rotation begins by identifying critical project elements from the Client Intent, Critical Activities, Lessons Learned categories. Drawings and Specifications still need to be considered given their contents are influenced by the other three categories, but these deliverables do not exist yet.

Client Intent in Development and Pre-Design

Uncovering intent requires skilled listening and open, honest communication. We may not recognize our client’s intent when we hear it – and they may not realize they are stating it. We need to ask questions that reveal what really matters.

“During the course of our discovery phase, my colleagues and I are going to be asking the hard questions about your vision for this project; questions involving motivations, what success looks like to you, what failure would look like, and how we will know with certainty that we have all stakeholders aligned.”

“It will take time for us to fully understand your true intent, and we may even need to help you articulate your intent in ways you may have not considered.”

“How does this facility help you achieve your business goals?”

“What does “good” or “success” look like to you?”

“What are the consequences of missing the mark?”

“What does the success of the new facility look like and what does the building need to be able to deliver at turnover?”

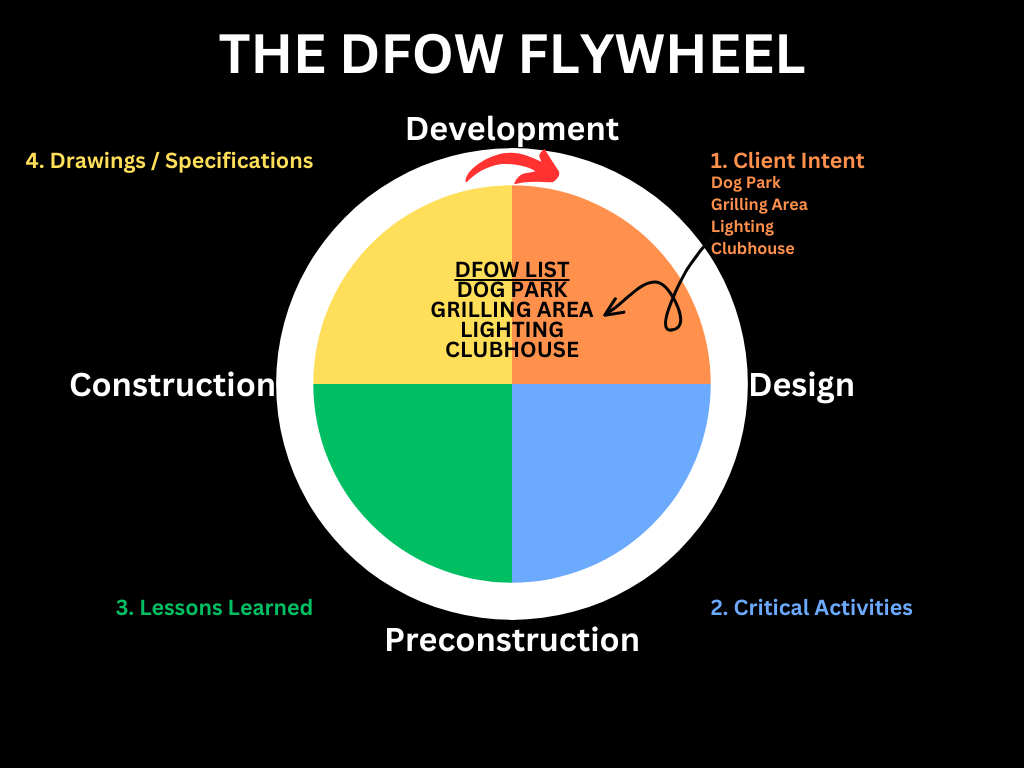

Let's start with a multifamily example where a client states:

"The building should have the same outdoor amenities as a luxury, single-family home."

To uncover intent, we might ask:

"Help us understand what you mean by ‘outdoor amenities’. A pickle ball court? Pool? Grill area?"

"Where would these amenities be located?"

"What's your vision for the lifestyle of future residents?"

The client might respond:

"We want functional amenities that residents are excited to use. Our target market is professionals who want a flexible, luxurious lifestyle. We want them to feel like they've made it in their careers when they walk through the building; to be excited to host friends. Definitely a grilling area, perhaps a dog park nearby. The light fixtures need to be high-end. We envision an open concrete area for grilling next to the clubhouse so residents can grill while watching sports on the clubhouse TVs."

From this conversation, we've identified several important elements:

Dog Park

Grilling Area (on a concrete amenity deck)

High-end Lighting

Clubhouse

Yes, everything else in a multifamily project still matters—fire protection systems must work, mechanical systems must operate. These are expectations, which must also be met. But to achieve true quality, intent must be delivered. Our challenge is giving special focus to what the client specifically values: the dog park, grilling area, lighting, and clubhouse. These items are added to the DFOW list via the DFOW Flywheel to document the conversation.

In our traditional approach, this conversation gets documented in meeting minutes or listed on a project brief alongside safety, schedule, and cost. As the project advances, focus naturally shifts to coordination and execution under mounting deadline pressure. A breakdown occurs because there’s no specification section for "outdoor amenities" as a complete experience. Individual equipment pieces have specifications, but the amenity area as a whole doesn't. Both design and construction teams treat all specification sections equally - concrete, elevators, mechanical systems - because contractually, they must deliver what's been specified. The result is that while everything is technically correct, the outdoor amenities don't match what the client envisioned, thus “quality” is not achieved.

The DFOW Flywheel allows us to tangibly focus on these elements by creating the list of DFOWs before design or construction begins, the idea being the list serves as a palpable handoff to the next project phase, guiding those team members on where to focus their energy. (Eventually, once construction starts, these DFOWs will proceed through a phased quality process.)

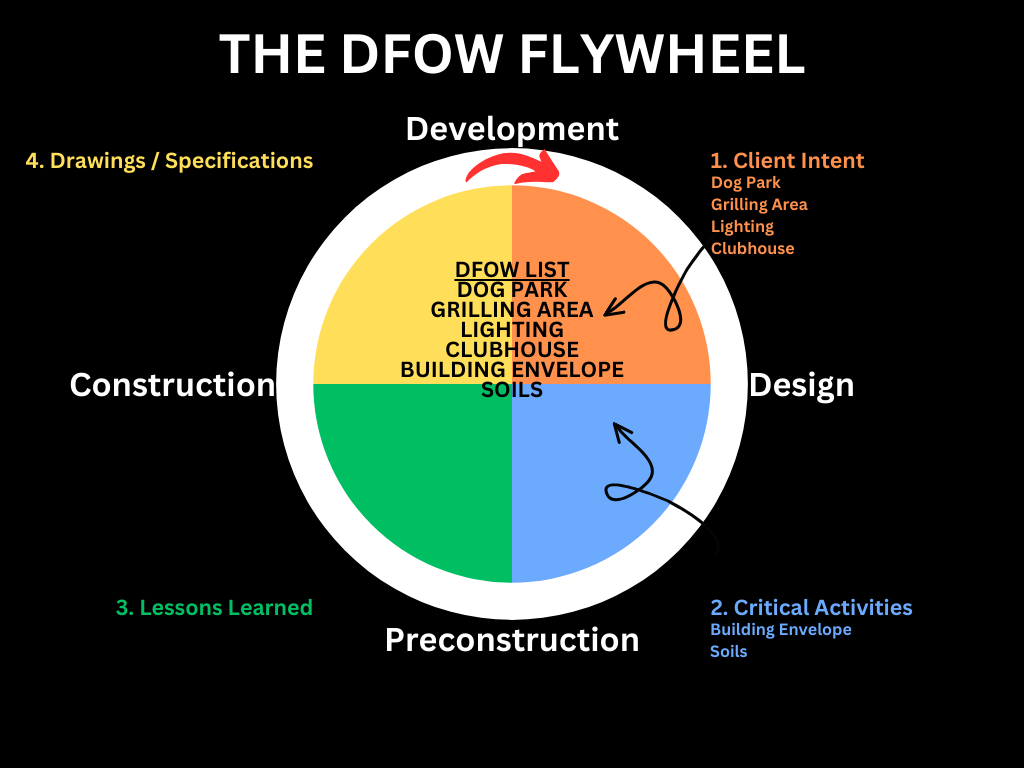

Critical Activities in Development and Pre-Design

Critical Activities includes any element of the project that is risky to install, or may be a critical element of the schedule. We traditionally view this from a construction lens, perhaps critical path activities or tasks that are deemed risky strictly from a safety standpoint. This perspective misses the point that other team members in earlier phases of the project not only would benefit from knowing this construction viewpoint, but that they also may have their own ideas of critical activities that construction needs to account for.

Continuing with our multifamily example, the designer may recognize that soils are often a problem in the region the client intends to locate the building. In addition, it may come up from an owner’s representative that one of the main risks in the industry is water damage, and that the design of the building envelope will be essential to the building’s longevity. (Note that the construction of the envelope will also be critical and should be part of the conversation.) This means soils and building envelope are also added to the list of DFOWs.

Getting to this requires that we think differently and outside our roles. A construction-minded designer or developer may ask:

“How are we going to build that?”

Project elements that generate that question fall are added to the DFOW list because they are Critical Activities for the project to get right. (See Lori Chandler’s Leadership Tactics interview for more on this.)

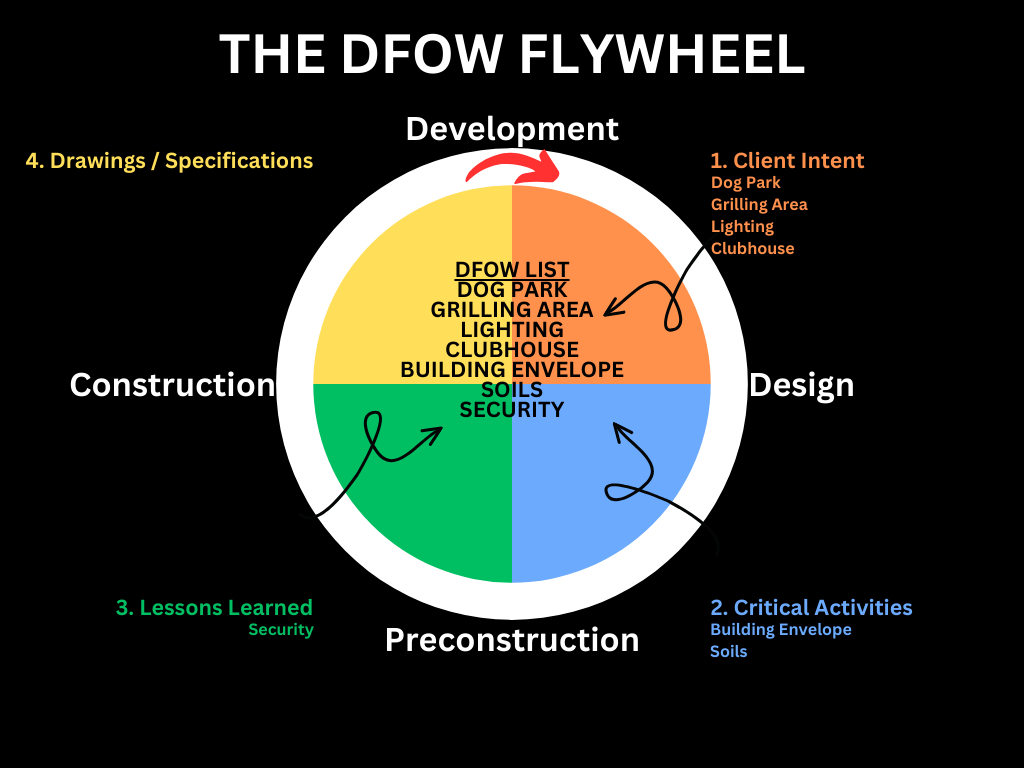

Lessons Learned in Development and Pre-Design

Organizing projects by DFOW recognizes Bent Flyvberg’s idea that projects are not unique, which allows us to apply our lessons learned across projects. It also solves the industry’s Lessons Learned problem by discussing learnings at the right time. I wrote about this previously in my article, How to Solve the Lessons Learned Problem in Design:

“There are two core problems with Lessons Learned in both design and construction: importance and timing. Importance: All Lessons Learned are treated with equal importance. Timing: Lessons Learned are shared at the wrong moment in time. [...] The team has no means to capture and compare information, and also lacks a strategy that outlines what Lesson Learned items deserve more focus and attention than others. Information is lost during project phase transitions because each discipline uses different language to establish their objectives. For example, design team members often use design intent to articulate important elements of the project, however design intent has little executable value to the construction project manager, superintendent, foreman, or electrician. Meanwhile, construction team members use terms such as Definable Features of Work (DFOW) to organize their work. [...] Information needs to be gathered into one place, organized in manageable chunks, and delivered to the right team member at the right time. These “manageable chunks” are Definable Features of Work. [...] The issue of knowledge transfer is solved by establishing the use of a common language early in the design process. [...] Effective Lessons Learned management requires more than just documentation—it demands strategic timing, prioritization, and a shared language across disciplines. By aligning design and construction teams under a common framework like Definable Features of Work, organizations can streamline knowledge transfer, reduce administrative burden, and focus on the most critical risks.”

I wrote this in the context of the design phase, but it applies to any project phase. Everyone in a project has learned something from prior experience. In the multifamily example, the client may have had security issues with their previous developments. Perhaps it was a specific product or an installation issue. The DFOW Flywheel gives the team a framework for discussing security, while focusing everyone’s attention on how to prevent those issues in the current phase.

The idea of the flywheel means the team is continuously reviewing the current list of DFOWs. If a Lesson Learned is not significant enough to show up as a DFOW, then it does not need to be discussed on the project.

Challenges in the Early Conversations

The traditional mindset will prevent the industry from improving. Criticisms to this idea might include:

Construction isn’t involved yet. There are other means to get construction involved earlier, regardless of the delivery method and contract type. A consultant can be hired with equivalent expertise. Leverage your contracting network. Ask for input.

What about design intent? Instead of thinking about design intent, we should recognize one intent - the client’s. Design intent items can be added to the list of DFOWs as well, however don’t call them design intent. We need one language with less terminology to describe what’s important on our projects.

The client doesn’t know how to articulate what’s important. We can ask questions and educate our clients on how to tell us what’s important to them - and we have tools to communicate visually with our clients. It’s our job to help them in this way.

DFOWs are only for construction. DFOWs can be used by any member of the project team if we are open to expanding our definition of what they are. (I wrote previously about this here.)

The reason I added the client intent element is because many clients are not regular builders and they often need our help to articulate what’s important to them. They may not know how to articulate their needs in a way a designer, developer, or contractor will understand. (That’s not the client’s fault.)

In Practice

Once these challenges are addressed, there are several tactics to implementing the DFOW Flywheel during these early project phases.

Intent Discovery Work Session. Hold work sessions where teams can dig deep on what the client truly needs as a result of the completed building. The building will serve a specific business purpose. Take time to prepare for this meeting, create a culture of transparency, and actively listen to what your client and associated stakeholders are saying - and what they are not saying. Keep cost and schedule out of the discussion. Be open to learning and education. The deliverable from this discussion is the list of physical building elements that are most important - the list of DFOWs.

Risk Awareness Matrix. Either in an existing meeting - or by holding a dedicated risk planning session - create a risk awareness matrix to identify Critical Activities that need to be planned for. Even if construction or equivalent expertise is not available, this is still a critical planning task. (Once construction is onboard, they can have a head start of knowing what activities are critical to the other team members during the construction process.) As I wrote in ASQ’s Certified Construction Quality Manager (CCQM) Body of Knowledge:

“When plans for mitigating risk are developed early, it is much easier to execute on them later. High impact risks create cost issues and schedule delays, and if those risks are properly forecasted, implementation is much more effective.”

Separate schedule, safety, and budget risks (such as permitting or weather) from risks associated with physical elements of the building. Permitting or weather would not become DFOWs as they are not physical elements of the project, yet still are risks to be mitigated (these are expectations rather than Client Intent or Critical Activities).

DFOW List Handoff. As the project progresses from discussion to discussion, always start with the list of DFOWs and confirm if they are still applicable, or others need to be added, or if anything can be combined with another DFOW, or if - based on new information - a DFOW no longer requires the attention the team thought it needed. The list is not static. The DFOW list is the primary handoff from Development and Pre-Design to Design. This gives the design team immediate guidance on where to focus their energy.

Conclusion

Establishing Client Intent is not a black and white science, rather an art in understanding your client. When we use the DFOW Flywheel, the DFOW list starts after the first conversation, becoming the main handoff from one project phase to another, helping each discipline focus their attention on what matters. The Development and Pre-Design phase establishes the initial momentum for the DFOW Flywheel by identifying and prioritizing the physical building elements most critical to project success

In Pre-Design and Programming, the team lead responsible for the primary client interactions would start the DFOW list, giving that to the design team as a starting point. The design team could later leverage the DFOW list for creating the Owner’s Project Requirements (OPR) and Basis of Design (BoD).

This approach transforms the relationship between client and project team from transactional to collaborative. Rather than simply documenting technical requirements, we become partners in designing and constructing physical environments that directly support business outcomes. The DFOW list becomes a focused, shared vision of success that’s constantly visible and regularly refined as the project progresses.

In the next article, we will explore how the DFOW Flywheel continues to build momentum through design and construction phases, focusing specifically on how this concept improves design reviews and helps construction planning.

Special Thanks

I started working on this idea of “Client Intent” and connecting it to Definable Features of Work nearly two years ago. This article has undergone more than twenty drafts, and I’m extremely thankful to Mike Jones, Randy Thompson, Jennifer Groen, and the late Scott West (you’re terribly missed) for their significant contributions to this idea and helping me improve my writing.

Thank you for reading!