Why Leaders Should Train

A Contrarian Opinion on Manager Responsibility

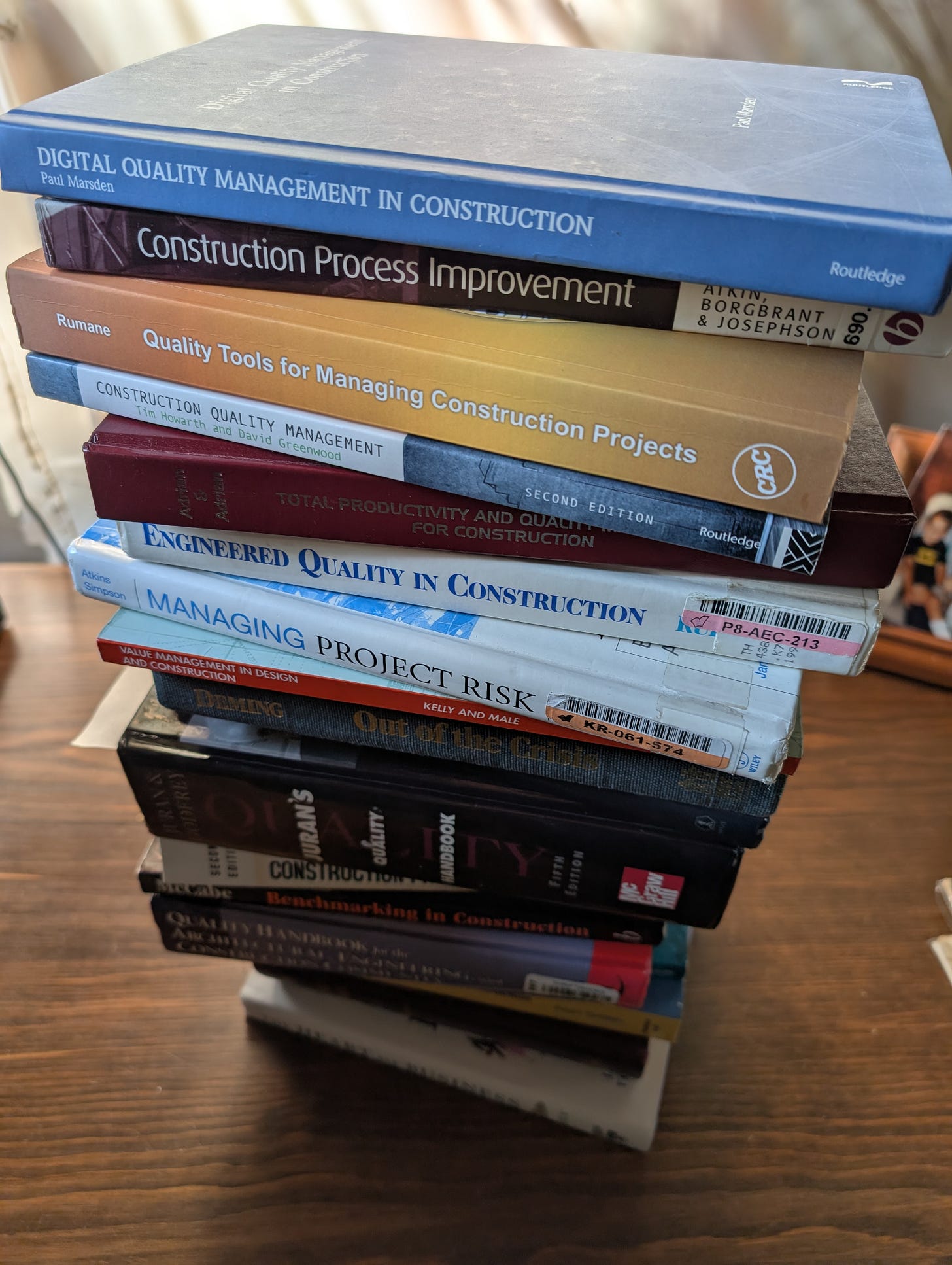

I read a ton of books on design and construction quality as I contributed to American Society for Quality’s (ASQ) Certified Construction Quality Manager (CCQM) Handbook. Of the 25+ I referenced, one I continue to reference weekly: “The Management of Quality in Construction,” by J.L. Ashford. Written in 1989, it is interesting that the ideas on quality 30+ years ago still resonate in 2025.

In the section designated for quality manuals and corporate documentation, Ashford stated on page 75:

“It is an unfortunate fact that many excellent managers and supervisors baulk at the task of producing written instructions for work for which they are responsible. They know what has to be done and can tell people what to do, but they lack the ability to organize their thoughts on paper. Quality managers are often pressed to prepare instructions for line managers who plead lack of time or resources to produce them themselves. Such pressures should be resisted. A quality manager who produces and issues instructions in respect of work for which he is not responsible is not only usurping the role of the manager who should be responsible, he is also collaborating in an activity which will inevitably weaken the work-force’s support for the system. It is a pre-requisite of success that production management should support the aims of the quality system and communicate this support to their subordinates. A production manager who, however unwittingly, portrays the attitude that procedures are the prerogative of some other person who is trying to impose additional burdens will soon find his work-force devising ways to frustrate the system rather than co-operating in making it work.”

When I read this three years ago, I was taken aback. Many hours are spent by quality managers writing and re-writing corporate quality systems, then teaching and training on the content. Currently, this is one of the main responsibilities of the modern quality leader or change agent.

But what if it shouldn’t be? What if this was the core responsibility of the manager?

In my own experience implementing quality systems, leaders informed me they did not have time to train on quality. That was the responsibility of the training and quality departments. (I’m not diminishing the role of dedicated training departments, rather working towards a mindset shift for leaders and managers of any discipline.) This idea applies to scheduling as well as other disciplines - the scheduling department trains on schedule, safety on safety. For the quality program, I was the primary trainer.

As I searched for information to either validate this or prove it wrong, I came across the following in “Engineered Quality in Construction” on page 137:

"Improved construction process quality must begin at the job site. Main office programs have proved inadequate for improving either construction processes or the completed product. The establishment of project site TQM [total quality management] programs is mandatory for making the industry-wide improvements that will move the industry forward once again."

That was written in 1994. It’s still a problem today.

What's typical for construction quality is a “main office program” that dictates how each project site should set up its project-specific quality plan. Both "The Management of Quality in Construction" and "Engineered Quality in Construction" make similar claims that the project teams and their management should be wholly responsible for developing their quality system for their job and writing the instructions for how to do it, teaching those on their team accordingly.

Many corporate quality leaders and managers request this of their teams, yet don’t make much progress. Instead, project teams ask for a quality process or a list of steps to follow to create their project-specific quality program. This puts responsibility on corporate quality to endlessly create the perfect process that is flexible enough to work for all projects. Yet once pushed out to the teams, the main complaint is it doesn’t work for the product type or region because that project is unique. These two forces continuously work against each other because project teams state they don't have time to create their own plan, meanwhile “corporate” can’t make a plan that works for everyone.

The problem we encounter is “corporate” will never know as much about the project as the project team does to build a quality plan that not only works for that specific project but is also simple and 100% effective. Quality managers receive feedback that they are “too corporate” for the project teams to understand or resonate with, or that they “don’t have the street credibility” to connect with the teams.

The interesting question to explore then is:

Would project-specific quality plans be simpler and more effective if project teams truly took full responsibility for writing work instructions for their own quality plans, creating those quality plans, and if leaders became trainers of quality, as they should with other disciplines?

It wasn’t until I read Andrew Grove’s High Output Management that I realized how to close the loop. In Chapter 16, appropriately titled “Why Training Is the Boss’s Job,” he notes the following, starting on pages 223 and 224:

“[…] For training to be effective, it has to be closely tied to how things are actually done in your organization. […] Employees should be able to count on something systematic and scheduled, not a rescue effort summoned to solve the problem of the moment. […] If you accept that training, along with motivation, is the way to improve the performance of your subordinates, and that what you teach must be closely tied to what you practice, and that training needs to be a continuing process rather than a one-time event, it is clear that the who of the training is you, the manager. You yourself should instruct your subordinates and perhaps the next few ranks below them. Your subordinates should do the same thing, and the supervisors at every level below them as well. […] Training must be done by a person who represents a suitable role model. Proxies, no matter how well versed they may be in the subject matter, cannot assume the role. The person standing in front of the class should be seen as a believable, practicing authority on the subject taught. […] We at Intel believe that conducting training is a worthwhile activity for everyone from the first-line supervisor to the chief executive officer.”

Powerful stuff.

Imagine the potential if everyone who utilized a system had to write the work instructions for themselves and train those they worked with. The cost spent by corporate overhead developing training programs would be greatly reduced if there was a greater involvement from production - along with higher understanding of those systems. This would also resolve the mentoring and knowledge transfer problem facing the industry.

Project Executives teach budgeting and client relationship management to Project Managers.

Superintendents teach scheduling, inspection processes, and team leadership to field crews.

Office and field leaders jointly teach quality systems, safety protocols, and schedule coordination to project teams.

Perhaps there is no right or wrong way. Everything depends on the context of the organization. However, when it comes to training and implementation, one method may be much more effective than the other.

Successful implementation of a system requires the leader to train on what they know - whether it’s quality, safety, schedule, budgeting, or any other skill they are responsible for. It’s a mindset shift for the industry, but one that is much needed.

Closing Note: Seth’s Blog had a great post noting an important prerequisite for training. You can read it here.